Protected land will positively impact drinking water for nearly 1 million North Carolinians downstream of the Yadkin River headwaters.

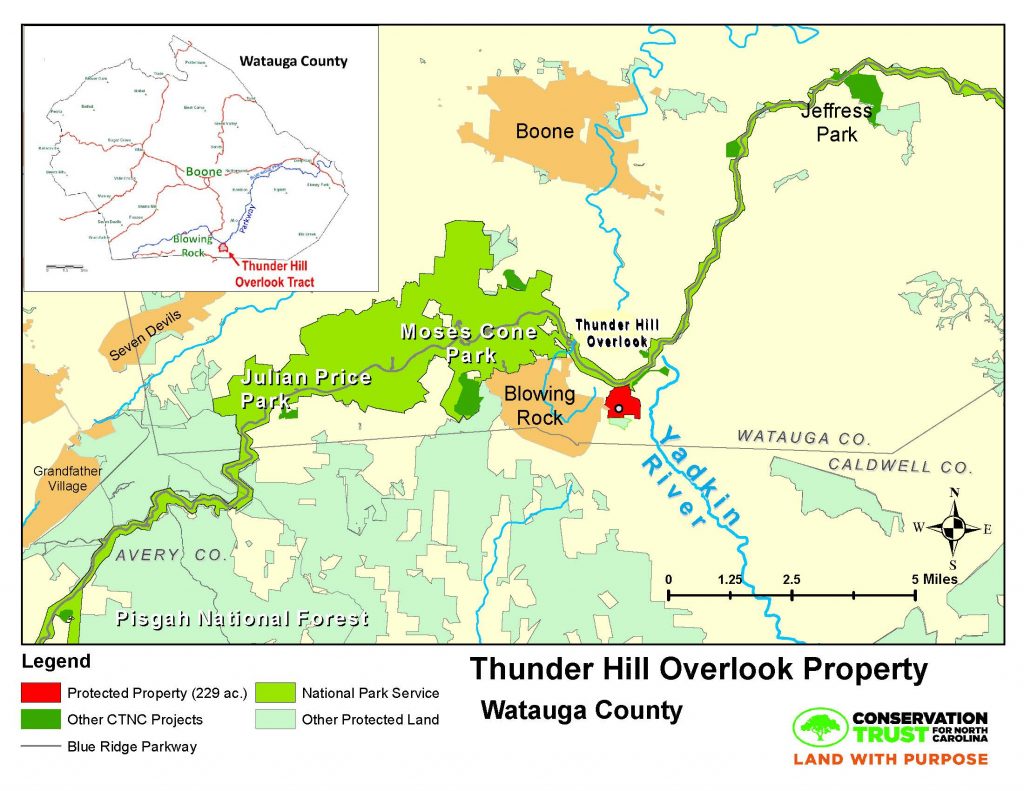

Thunder Hill Overlook, a 229-acre tract of land on the outskirts of Blowing Rock, N.C., is permanently free from subdivision, development, and logging after being conveyed to the National Park Service for inclusion in the Blue Ridge Parkway boundary by the Conservation Trust for North Carolina (CTNC).

The Thunder Hill Overlook property is highly visible from the Blue Ridge Parkway between mileposts 290 and 291, and can be viewed from both the Thunder Hill and Yadkin Valley overlooks. This is a significant acquisition for the region with numerous unnamed streams and Martin Branch, one of the primary streams forming the headwaters of the Yadkin River.

“As the surrounding towns of Boone and Blowing Rock continue to grow, conserving parcels of this significance is increasingly important. The land not only supports significant wildlife habitat, but also holds the headwaters of the Yadkin River, a water system that supplies provides drinking water to almost one million North Carolinians across 21 counties and 93 municipalities.”

CTNC Executive Director Chris Canfield.

CTNC’s purchase of the property was made possible by a generous price reduction offered by the sellers, Howard B. Arbuckle lll, Corinne Harper Arbuckle Allen, Anne McPherson Harper Bernhardt, Lee Corinne Harper Vason, Mary Gwyn Harper Addison, and Albert F. Shelander, Jr., heir of Betty Banks Harper Shelander, and significant contributions from a number of private donors including Fred & Alice Stanback and other local conservation enthusiasts.

Finley Gwyn Harper, Sr., was born in 1880 near Patterson, Caldwell County, in the scenic Happy Valley area of North Carolina. He grew up in his birthplace with his 5 siblings, and, except for time spent earning his college degree in Raleigh (now N.C. State University), he lived his entire life within 25 miles of Patterson. His grandfather had given land for the founding of Lenoir and many descendants were active in the business, civic, and social activities of northwestern North Carolina. In 1905 when he was 25 years old, Gwyn Harper, Sr., acquired the first of several tracts which form the Harper lands in Blackberry Valley. Two years later, he married Corinne Henkel who also grew up in Happy Valley and Lenoir. Through the years he continued to purchase additional adjoining parcels, some of which were original land grants from the state. The last deeds for his assemblage are dated in the late 1940’s shortly before his death in 1951. Gwyn Harper, Sr., and his wife, Corinne, loved the rolling hills, rivers, ridges, valleys and views of the Blowing Rock area. Their story reflects the sentiments of the extended family who also have treasured these pristine mountain lands and waters. The direct descendants of F. Gwyn Harper, Sr., have continued to hold his acreage for 68 years since his death.

“We, the current owners, are pleased and humbly grateful to convey the Harper lands to the Conservation Trust for North Carolina for protection by the National Park Service as a part of the Blue Ridge Parkway while also providing permanent protection to wildlife and water quality in this beautiful region of western North Carolina,” the sellers shared in a joint statement. “We express our sincere, heartfelt thanks to the Piedmont Land Conservancy, Foothills Conservancy, and, in particular, Conservation Trust for North Carolina for working cooperatively, collaboratively, and professionally to make preserving this unique property a reality.”